Affecting one in ten adults, diabetes is the most common endocrine disorder and was the seventh leading cause of death in the United States in 2015. People with diabetes have abnormalities in carbohydrate metabolism characterized by elevated blood sugar levels. This condition involves a relative or absolute deficiency in insulin secretion, alongside varying levels of insulin resistance. Diabetes is a systemic condition with impacts on multiple organ systems, including the gastrointestinal tract. Therefore, a comprehensive pre-anesthesia evaluation of diabetic patients should encompass not only their diabetes history but also related organ systems, such as an assessment of the risk of diabetic gastroparesis.

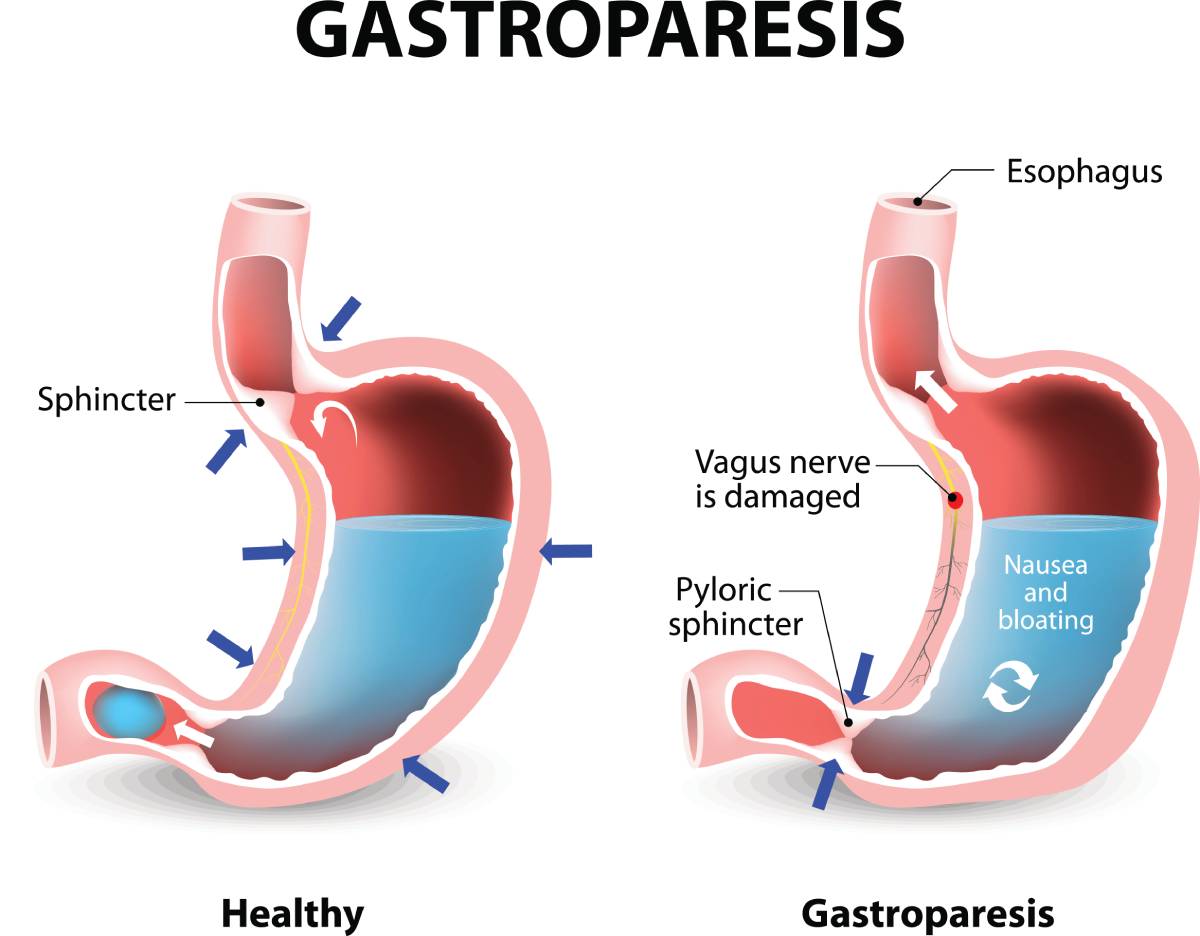

Gastroparesis, a condition characterized by delayed stomach emptying, is commonly associated with diabetes. The estimated incidence of gastroparesis in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes over ten years is 5.2% and 1%, respectively. Gastrointestinal complications typically manifest in patients who have had diabetes for more than five years. Abnormalities in gastric emptying include impaired postprandial gastric accommodation and contraction, as well as reduced frequency of contractions. These abnormalities primarily result from dysfunction in the gut’s intrinsic nervous system, such as the interstitial cells of Cajal. Symptoms of gastroparesis, such as nausea, vomiting, early satiety, postprandial fullness, abdominal pain, or bloating, should raise suspicion of the condition. Unlike some other diabetic complications, gastroparesis is not progressive, and treatment aims to alleviate symptoms. Treatment includes improving glycemic control, dietary adjustments, antiemetic and prokinetic medications, endoscopic therapies, and surgery.

The American Diabetes Association recommends screening for diabetic autonomic dysfunction at the time of type 2 diabetes diagnosis and five years after type 1 diabetes diagnosis, with annual history and physical exams for signs of autonomic dysfunction. When a patient with diabetes is scheduled for surgery, it is important for the pre-anesthesia evaluation to review the results from any previous diabetic gastroparesis screenings. Diabetic complications affecting the gastrointestinal tract can lead to gastroesophageal reflux disease and/or gastroparesis, both of which increase the risk of aspiration during anesthesia induction. Therefore, patients should be asked about the presence of related symptoms such as heartburn, regurgitation, early satiety, bloating, nausea, vomiting, or abdominal pain. Patients with these symptoms may require extended preoperative fasting and sometimes may require rapid sequence induction and intubation to minimize aspiration risk.

Severe diabetic gastroparesis might necessitate awake intubation for general anesthesia, especially in patients with airway management difficulties. Patients with constipation due to gastroparesis may benefit from multimodal postoperative analgesia with reduced opioid use, as opioids can exacerbate problems with gastric motility. Additionally, diabetic gastroparesis is linked to an increased risk of obstructive sleep apnea and/or central sleep apnea. Sleep apnea heightens perioperative risks and should be suspected, identified, and managed to minimize postoperative complications.

The need for and frequency of blood glucose monitoring during anesthesia depends on the surgery’s length and timing, preoperative blood glucose levels, and medication. Sedation and general anesthesia can mask hypoglycemia symptoms, necessitating frequent blood glucose monitoring. Hypoglycemia treatment medications, such as dextrose and glucagon, should be readily available. Blood glucose levels are typically monitored every few hours. While continuous glucose monitoring can be beneficial for self-monitoring in diabetes management, its role during anesthesia remains unclear, with limited literature existing on the subject.

Overall, patients with a history of diabetes require a diligent preoperative evaluation to ensure that risk-management strategies (e.g. prolonged fasting, rapid sequence protocols, glucose monitoring) may be employed during the perioperative period.

References

- Lacy BE, Parkman HP, Camilleri M. Chronic nausea and vomiting: evaluation and treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018 May;113(5):647-659. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0039-2. Epub 2018 Mar 15. PMID: 29545633.

- Parkman HP, Hasler WL, Fisher RS; American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the diagnosis and treatment of gastroparesis. Gastroenterology. 2004 Nov;127(5):1592-622. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.055. PMID: 15521026.

- Camilleri M, Kuo B, Nguyen L, Vaughn VM, Petrey J, Greer K, Yadlapati R, Abell TL. ACG Clinical Guideline: Gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022 Aug 1;117(8):1197-1220. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001874. Epub 2022 Jun 3. PMID: 35926490; PMCID: PMC9373497.

- Gustafsson UO, Thorell A, Soop M, Ljungqvist O, Nygren J. Haemoglobin A1c as a predictor of postoperative hyperglycaemia and complications after major colorectal surgery. Br J Surg. 2009 Nov;96(11):1358-64. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6724. PMID: 19847870.

- Dronge AS, Perkal MF, Kancir S, Concato J, Aslan M, Rosenthal RA. Long-term glycemic control and postoperative infectious complications. Arch Surg. 2006 Apr;141(4):375-80; discussion 380. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.4.375. PMID: 16618895.

- Han HS, Kang SB. Relations between long-term glycemic control and postoperative wound and infectious complications after total knee arthroplasty in type 2 diabetics. Clin Orthop Surg. 2013 Jun;5(2):118-23. doi: 10.4055/cios.2013.5.2.118. Epub 2013 May 15. PMID: 23730475; PMCID: PMC3664670.

- Lluch I, Ascaso JF, Mora F, Minguez M, Peña A, Hernandez A, Benages A. Gastroesophageal reflux in diabetes mellitus. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999 Apr;94(4):919-24. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.987_j.x. PMID: 10201457.

- Feldman M, Schiller LR. Disorders of gastrointestinal motility associated with diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 1983 Mar;98(3):378-84. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-98-3-378. PMID: 6402969.